Stanley William Dyson, the only child of Edith Rose Dyson [née Nicholson] and William Bielby Dyson was born in York on 30th April 1895.

His early life was marred by a double tragedy as his mother committed suicide on 30th August 1903; in the words of the coroner by ‘cutting her throat with a razor’. Two days later after giving evidence at the inquest ‘in a very feeble condition’, his father had a fatal seizure in his hotel room and died. Orphaned at just 8 years old, Stanley was subsequently raised up by his late father’s sister, Agnes Moorhouse and her husband, alongside their own son Arthur John Moorhouse in Cheshire.

Agnes Moorhouse chose to send her young nephew to Wellington College1 to be educated and whilst there Stanley was a member of the Officers Training Corps [OTC]. He also played cricket for the 1st XI and 2nd XI association football. He left the college in 1912 to take up a place at Manchester University.

Whilst at University he was a member of the OTC contingent and in December 1914 had been accepted for the Honours’ School of Chemistry; a place he was unable to take up as the call of duty intervened. Stanley attended the recruiting station at 30 Dickenson Street in Manchester as he was living in the city at the time. Whilst he was accepted by the army the medical officer considered him to be more suited to departmental work due to his ‘poor eyesight’.

On 18th December 1914 Stanley was commissioned as a temporary Second-Lieutenant in the 11th (Service) Battalion, The Manchester Regiment, and for the first few months of his service life remained in and around Aston-under-Lyme. In April 1915 the Battalion was moved south to Witley camp, near Godalming in Surrey.

In June that year they received orders to prepare for the embarkation to Gallipoli and duly sailed out of Liverpool Bay on 30th June en route to Mudros before their final destination: SUVLA BAY, where they arrived on 6th August 1915.

Gallipoli is the name given to the peninsula west of the Dardanelles Straits, and the overall campaign that took place there between April 1915 and January 1916. It entered into Australian and New Zealand folklore as the place where the soldiers of the 1st ANZAC - the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps - first saw action during the War, and to many of its peoples, when their countries came of age.

Some forget, given the rightful place that the memory of Gallipoli has in Australia and New Zealand, that it was not purely an ANZAC operation. The rest of the British and French armies deployed there outnumbered the ANZACs both in terms of men deployed and casualties sustained, but these two European countries, unlike their New World counterparts, were used to battles with enormous casualties.

The terrain was totally inhospitable, being a rocky, scrub-covered area with little water to speak of. Its hills were steep-sided, cut into ravines and deep gulleys. Among the hills were many peaks and valleys.

Conditions on Gallipoli defied description, rarely reflected in letters home to loved ones. The terrain and close fighting did not allow for burial of the dead and so corpses were everywhere leading to flies and other vermin to feast on the remains in the incessant heat; sickness amongst the soldiers was rife. In October 1915 the winter storms caused damage and hardship, two months later a blizzard followed by a thaw caused casualties of approximately 15,000 men throughout the British contingent Of the 213,000 British casualties on Gallipoli, 145,000 were due to sickness; the top three being diarrhoea, dysentery and enteric fever.

After four months of hell on earth the order was given to evacuate and on 19th December 1915 Stanley and his Battalion began the two day process of extracting themselves to Imbros; the evacuation of their positions and that of the whole Allied force over the following fortnight was undertaken virtually without loss.

On 26th January 1916 the Battalion began the move to Egypt where it landed at Alexandria on 2nd February and a week later had concentrated at Sidi Bishr. A few days later they took over a section of the Suez Canal and its defensive fortifications where they remained for the next four months.

On 17th June orders were received that the Battalion was needed in France and on 3rd July they boarded ship at Alexandria and sailed to Malta where, after a brief pause for provisioning, they departed for Marseilles on 6th July. After their arrival in Marseilles they embarked on the long train journey up through France and finally arrived in the trench lines on 19th July 1916 tired and exhausted.

Stanley received his promotion to First-Lieutenant on 17th September 1916 with a further promotion to acting Captain on 20th July 1917.

On 2nd October 1917 the Battalion left their position at DIRTY BUCKET camp and moved into the line astride the POELCAPPELLE–ST JULIEN ROAD. At dusk the following day forming up tapes and discs were put out with the whole Battalion formed up on the tape by 4.40am, 4th October.

The Battalion War Diary2 detailed the following:-

6am ‘Zero’. The Battn advanced to the opening barrage in perfect order. In some cases individuals got too close to our barrage and were hit.

6.38am. The dotted RED LINE [interim objective] was captured under the barrage. During this advance very little opposition was encountered but a goodly number of the enemy were killed especially in the forward line of shell holes. MALTA HOUSE presented no difficulty & some defenders in the shelters nearby were easily disposed of by 2/Lt PEARSON with his […]. While the protective barrage was on the DOTTED RED LINE there was considerable activity on the enemy’s part some of the latter attempted a feeble counter attack, but were soon disposed of by Lewis Gun & rifle fire and during the last few minutes of the protective barrage we inflicted heavy casualties on them as they attempted to flee. The pause on the DOTTED RED LINE enabled the leading companies to re-organise & to correct a slight deviation to the right, caused perhaps by the 7th S STAFFS on our left.

The advance to the RED LINE was hampered a good deal by machine gun fire coming from POELCAPPELLE, firstly coming from the direction of the CHURCH and afterwards from the BREWERY, but the RED LINE was captured under the barrage.

8.34am. GLOSTER FARM […] under the barrage and presented no serious obstacle – most of the occupants having been killed apparently by our Trench Mortars. Several Machine Guns were captured here & these were used against the enemy (who could be seen retiring) by the party detached to garrison the place, and by a section of Machine Gunners attached to the Battn. After capture of RED LINE patrols went out under our protective barrage to clear the ground of enemy.

The advance of GLOSTER FARM was headed by a tank which afterwards captured TERRIER FARM.

Sporadic counterattacks were attempted by the enemy throughout the afternoon but these came to nothing and were dealt with by artillery, LG & MG fire.

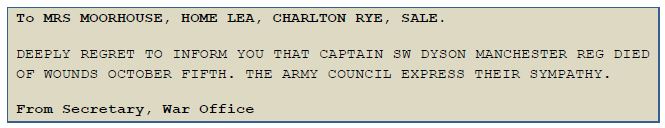

At some point during a full frontal assault on an enemy position Captain Stanley William Dyson, 11th (Service) Battalion, The Manchester Regiment, sustained a bomb wound to the abdomen and was evacuated back to No.47 Casualty Clearing Station [CCS]. He died of his wounds the following day, Friday 5th October 1917 at the age of 22, and by the time his aunt had received notification of her nephew’s injuries at her house in Sale, Stanley was dead.

The final telegram arrived on 7th October.