Alec Edmund Stuart Hodgson was born in Headingly, Yorkshire, on 7th September 1898 to Marion Helen Hodgson [née Knight] and her husband Edmund John Hodgson. Another child did not survive past infancy.

Stuart’s father’s occupation was a glass merchant with his mother taking up the position of Housekeeper and Matron to the founder of Wellington College, John Bayley in 1901. Whilst Stuart lived on the premises from the age of 3 he was only a pupil at the school1 from 1911-14, associating himself with productions by the College Dramatic Society and serving in the Officers Training Corps [OTC] as a Lance Corporal [Acting Corporal]. He left to study electrical engineering, living in Wolverhampton, with the intention of going up to Birmingham University a couple of years later.

On 23rd March 1915 whilst still in Wolverhampton Stuart travelled north to Roker, Sunderland where he applied for a commission in the Special Reserve of Officers with a preference for the York and Lancaster Regiment. He appears to have deliberately omitted his date of birth from his handwritten application, although a date of 7th September 1886 was added by another hand at a later date, and then later still the year 1896 in a circle! As Stuart was under the age of 21 the form required the countersignature of a parent, and it was his mother who performed this task. Proof of birth was a firm requirement for an officer candidate and they were required to submit, either with the application itself, or at a date soon thereafter, an original birth certificate or a certified copy; the penalty for dishonesty could be quite severe.

His certification of ‘good moral conduct’ was completed by his local GP from Wolverhampton, together with John Bayley himself, who wrote “Hodgson will do his utmost to succeed and that he will be firm and gentlemanlike”.

Stuart was subsequently commissioned on 29th March 1915 as a probationary Second-Lieutenant into the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, The York and Lancaster Regiment, being the depot/training unit of the Regiment who at the time were in Roker. Here he remained until his arrival in France on 12th October 1915 with a posting to the 2nd Battalion, one of the two regular Battalions of the Regiment.

Writing back to his old school towards the end of 1915 Stuart wrote:

We have just come out of the trenches, having had six days in. We have been fairly lucky this time, and I have not had a great number of casualties. I must say I felt a bit queer when I saw the first man fall. The trenches are so bad now that we keep moving about every two days. Some, naturally, are much worse than others, and we went into some where the water was right up to the waist.

We are fitted with gum boots reaching to the thigh, but even then we often get very wet. The winter is now coming into great prominence. We have had several hail storms, and every night there is a heavy frost, which makes things rather unpleasant to work, as you know we work all night and try to sleep by day.

He received confirmation of his rank on 8th January 1916 at POPERINGHE, moving to FORWARD COTTAGE a few days later. Whilst in the trenches there they were susceptible to enemy shelling but fortunately the casualties were reasonably light and here they remained until 23rd January when they relieved the 8th (Service) Battalion, The Bedfordshire Regiment [8BEDS] at BURGOMASTER FARM and CANAL BANK. On 25th January the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte were sending over various aircraft on reconnaissance flights providing elusive targets for the soldier’s rifles.

As January turned into February the Battalion was spending its time between FORWARD COTTAGE and POPERINGHE where, from time to time, enemy aircraft would drop bombs on the town. The first week of March saw the Battalion billeted in various cellars within the town of YPRES which was slowly being destroyed on a daily basis by enemy shell fire, before they moved to new positions in the RAILYWAY WOOD sector, occupying themselves with night time patrols and holding the line.

At the end of March they returned to POPERINGHE where they entrained for Calais and some much needed rest and reorganisation and where they could take part in some sport; swimming in the sea and the Brigade gymkhana which was a great success.

By 16th April Calais was but a distant memory and the Battalion was now back at CANAL BANK where it was pretty wet and miserable. Sometime over the 19th/20th April whilst the Battalion was supporting the 8BEDS during an attack in the MORTELDJE salient Stuart was injured to the extent that he was repatriated back to England.

During his period of convalescence he was posted back to 3rd (Reserve) Battalion where he was able to undertake light duties. Eventually his medical board pronounced him fit again and he returned to the Front in September 1916 posted to ‘B’ Company, 2nd Battalion.

On 8th October the Battalion went back into the line and two days later, together with six Vickers Machine Guns from the Brigade Machine Gun Company [MGC], was in MISTY TRENCH and the new support line between the Front Line and RAINBOW TRENCH. With various other Battalions around them, or in the reserve, they were subjected to heavy shelling and intermittent direct and indirect Machine Gun fire which continued through the night.

At 7.00am on the following day bombardment of the enemy lines commenced and then continued throughout most of the day but at 3.15pm a ‘Chinese’ attack lasting some 10 minutes started. This consisted of a barrage coupled with heavy artillery fire. After the 10 minutes had elapsed, the barrage ceased and ‘normal’ bombardment continued. The enemy responded by sending over a barrage of their own.

The morning of Thursday 12th October 1916 saw the recommencement of what was termed ‘The Battle of Le Transloy’ by the British Fourth Army and the French VI Army on its right flank. It was the final offensive mounted by the Fourth Army during the 1916 Battles of the Somme, the outcome of which was considered to be inconclusive.

The adjutant later recorded in the War Diary2 the events of 2.25pm that afternoon.

Twenty minutes after the advance of the 4th Divn on the right, the 2/York & Lancaster Regt advanced to the assault from the 6th Divn front line; the 71st Bde on the left stood fast in CLOUDY TRENCH.

Immediately an intense machine gun barrage was laid by the enemy on the 16th I.B. front line. The first wave advanced a distance of from 50 to 80 yds suffering exceedingly heavy casualties: the remainder of the battalion not casualties found shelter in shell-holes and returned to the original front line after dark.

A large number of casualties occurred actually whilst the regiment was getting out of the front line to the assault. Thus of the fifteen officers who went into the line on the evening of the 8th October only 5 remained.

The Battalion casualties for the day when the roll was finally called amounted to 3 Officers killed and 4 wounded; Other Ranks 57 killed, 130 wounded and 33 missing.

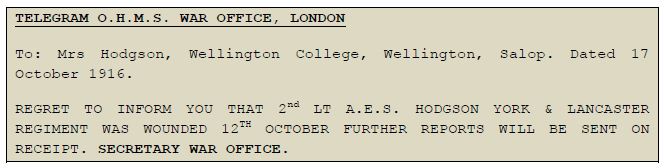

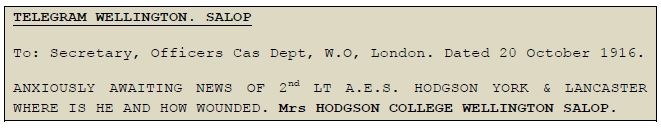

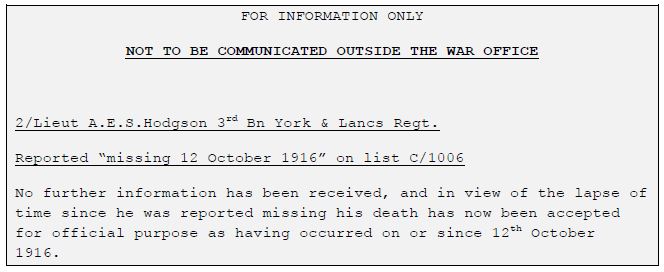

Initially the official record listed Second-Lieutenant Alec Edmund Stuart Hodgson, 2nd Battalion, The York and Lancaster Regiment, as ‘killed in action’ [KiA], but this was then struck out and amended to ‘wounded’, thus leading to some confusion within the military, additional distress to the family which in turn led to various enquiries to determine his fate.

By amending the record from ‘KiA’ to ‘wounded’ initiated the War Office to despatch the following telegram to Stuart’s mother at Wellington College.