Victor Louis Snelson was born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire on 11th August 1896 the only son of Annie Snelson [née Roberts] and Edward Rivington Snelson. Their only daughter, Winifred Annie Snelson was born in July, the year before. Victor’s father was a tobacconist and shopkeeper by trade.

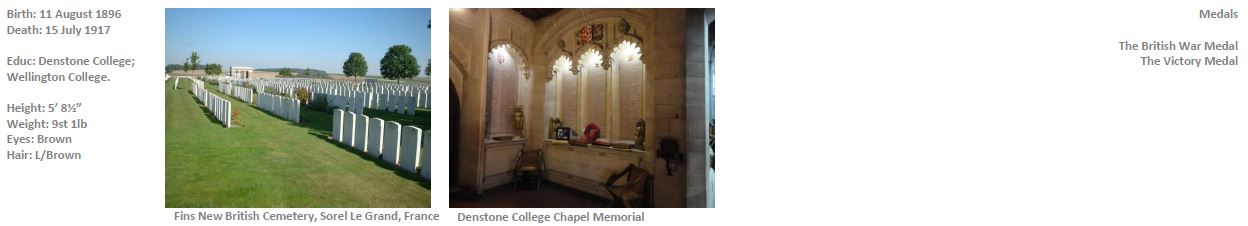

His parents initially sent Victor to Denstone College to be educated and he was in Meynell House from 1907-10 where he was described as a quiet and retiring boy with grit. After leaving Denstone he then attended Wellington College1 where he was a member of the Officers Training Corps [OTC].

After leaving school Victor worked alongside his father as a tobacconist before signing up as Private [13030] Louis V. Snelson2 with the 7th (Service) Battalion, The King’s (Shropshire Light Infantry) in Shrewsbury, assigned to ‘D’ Company. Whilst with the 7th Battalion Victor was stationed in England.

In the summer of 1915 Victor submitted his papers for a temporary wartime commission in the army and for his character witnesses selected the curate of St. Chads, the Chief Constable of the county and John Bayley, his old school principal at Wellington College.

On 24th September he was discharged to a commission as a Second Lieutenant with the 12th (Reserve) Battalion, The Welsh Regiment, at their permanent base in Kimmel Park, Rhyl in North Wales. In September 1916 the Battalion was converted into the 58th Training Reserve Battalion of 13th Reserve Brigade and in so doing lost its connection to The Welsh Regiment.

A few weeks after this conversion in October 1916, Victor was posted on ‘attachment’ to 12th (Service) Battalion (3rd Gwent), The South Wales Borderers and prepared to embark for France where his new ‘Pals’ Battalion had been fighting since the summer.

The South Wales Borderers was an infantry regiment of the British Army. It was initially raised as the 24th Regiment of Foot in 1689, but it was not until 1881 that it gained the name of The South Wales Borderers. In 1879 the Regiment marched into history when both of its battalions took part in the Zulu War. The first engagement took place at Isandlwana and the second, more famous; the stand at Rorke's Drift.

The stand at Rorke's Drift, immortalised in the 1964 film “Zulu”, saw the award of 11 Victoria Crosses [VC], with no fewer than 7 VC’s, (including one for the most senior officer of the Regiment present, Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead, played in the film by Michael Caine): the most ever received in a single action by one regiment. The Battle of Isandlwana was dramatized in the 1979 film “Zulu Dawn”.

Not long after his arrival in theatre Victor was sent to ‘Camp 21’ where he received instruction in the use of the Lewis Gun and how best to deploy it to maximum advantage; then in February 1917 he attended a Divisional course at ALLERY whilst the Battalion was located at SAILLY LAURETTE.

By mid-April the Battalion was based at ETRICOURT when they received orders for an imminent attack on FIFTEEN RAVINE, part of an overall operation against the HINDENBURG LINE, with the intention of capturing and consolidation the enemy position. ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies were to lead the attack with ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies in support.

The twenty-four hours before the attack was quiet, with the exception being the move of ammunition and bombs to the forward positions in readiness for zero hour, fixed for 4.20am on the 21st April. To support the Battalion in their endeavours they had 19th Royal Welsh Fusiliers on the right and 13th East Surreys on their left flank. At 3.15am the attack formations moved into their starting positions, with each man the correct interval apart from his neighbour, and then at zero hour the British artillery bombardment commenced and was maintained until 5.15am.

Using the bombardment as protective cover soldiers of the Battalion moved forward only to be met by incoming shrapnel and high explosives fired off by the Germans. At around 5.00am the advance was temporarily checked by enemy snipers. After they had been taken out the attackers entered the ravine at 5.15am, all the while still under heavy Machine Gun [MG] and rifle fire, until they too were silenced. A number of prisoners were taken in addition to the killed and wounded. British casualties were not considered too severe; Victor was not among them.

At the beginning of May, in what was glorious weather for a change, the British artillery was busy trying to destroy some of the enemy wire around the village of LA VACQUERIE in readiness for a proposed attack a few days hence. There was also a considerable amount of aerial activity in the skies above and at night the Germans destroyed and burnt property so as to deny them to the British in anticipation of an attack. A night-time patrol was also sent out from the Battalion on 4th May with the purpose of checking the enemy positions and their strength in numbers. A prisoner was captured, who did not take much persuading to divulge the information in his possession regarding the strength and disposition of his fellow Germans.

Around 4.00am the captured information was put to the test and a ‘trial’ barrage was launched by the British artillery to test the enemy response, thereby determining how soon, and where, the Germans would retaliate if under a real attack. The ruse worked and very little damage was done by the incoming shells. The adjutant noted ‘His reply was feeble!’

The real attack was launched on 5th May 1917 on the village of LA VACQUERIE. Victor and his Battalion were positioned on the right of the front line with the objective of inflicting loss to the enemy, damage his defences and to obtain identification and any relevant material; e.g. letters, maps etc, they could scavenge. The Battalion was supported in its endeavours by one from The Royal Welsh Fusiliers who provided ‘mopping-up’ parties and carriers for the Trench Mortar Batteries. Covering fire was laid down by 119 Brigade Machine Gun Company and the 119th Trench Mortar Battery. In the rear the 224th Field Company, Royal Engineers destroyed any concrete bunkers and cellars that the infantry were unsuited to deal with. There is no record of the number of Battalion casualties: a total of 8 Military Medals [MM] were later awarded to the NCO’s and men of the Battalion.

As fighting raged in northern France the contrast between it and the south was very pronounced and the War Office realised very quickly that arrangements needed to be put in place for soldiers to convalesce and rest outside the theatres of war; a task that the British Red Cross was ideally placed to facilitate. On the French Riviera in the south, philanthropic families appropriated large houses and hotels to serve as military convalescent homes and nurses’ rest homes. The first convalescent home was opened in Cimiez and funded by Lord Michelham and received its first patients at the end of 1914 with Lady Michelham initially running the hospital personally.

It is believed that Victor Snelson spent time in one of the Michelham Convalescent Homes between 6th and 27th June 1917 but the reasons behind his brief stay are unclear, as too is the exact location of the home.

On the 8th July Victor re-joined his Battalion who were now at GONNELIEU toiling under wet and stormy conditions, where they were undertaking some physical training, and providing working parties behind the lines as well as practicing their bayonetry. A number of luminous scopes had been delivered to the Battalion which were fitted to some of the soldier’s rifles.

The Battalion had re-entered the line by 11.30pm on 13th July, taking over from a unit of Royal Welsh Fusiliers without any incident. However, whilst out on patrol the following day, Second-Lieutenant Victor Louis Snelson, 12th (Service) Battalion (3rd Gwent), The South Wales Borderers, on detachment from The Royal Welsh Regiment, was shot and he later died of his wounds on Sunday 15th July 1917; he was just 20 years old.

In a letter to his family, his Commanding Officer, Lieut-Colonel Robert Benzie, DSO* wrote:

He had re-joined us only a few days ago. He was a very unassuming, promising, keen, and capable young man, held in high esteem, and respected by all ranks. His loss is deeply felt throughout the battalion.

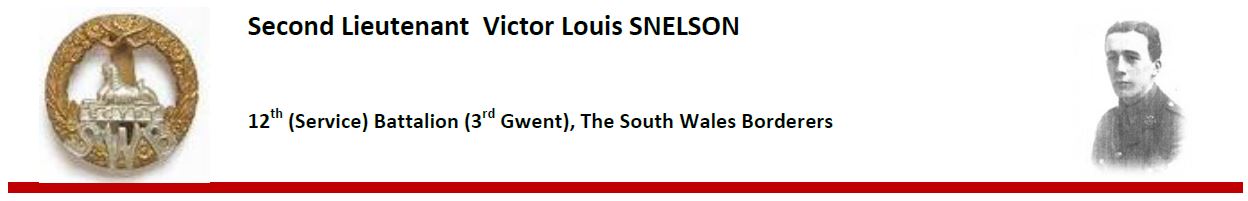

Victor was buried in Fins New British Cemetery, Sorel Le Grand, where he lies alongside 1,288 other First World War casualties, of who 208 remain unidentified. In addition Victor Snelson is also commemorated on the Meole Brace Memorial in Shropshire and on the imposing memorial to the fallen in the chapel of Denstone College.

The South Wales Borderers Regiment is perpetuated today in the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Welsh Regiment.